My friend Molly has had an impressive career. She got a job as a software engineer after graduating from college, and after kicking ass for a year or so she was offered a promotion to management, which she accepted with relish. Molly was smart, driven, and fiercely ambitious, so she swiftly clambered up the ranks to hold director, VP, and other shiny leadership roles. It took two decades, an IPO and a vicious case of burnout before she allowed herself to admit how much she hated her work, and how desperately she envied (guess who??) the software engineers she worked alongside. Turns out, all she ever really wanted to do was write code every day. And now, to her dismay, it felt too late.

Why did it take Molly so long to realize what made her happy? I personally blame the fucking hierarchy.

The Hierarchy Lie

The “Big Lie” of hierarchy is that your organizational structure is a vertical tree from the CEO on down, where higher up is always better.

Of course any new grad is going to feel that way, on the heels of 15-20 years spent going through school year by year, grade by grade, measuring success via good grades and teacher approval. The early years of professional life are a similar blend of hard work, leveling up and basic skills acquisition. (They got Molly hopped on the leveling treadmill before she even had a chance to become a real adult, in other words. 😍)

approval. The early years of professional life are a similar blend of hard work, leveling up and basic skills acquisition. (They got Molly hopped on the leveling treadmill before she even had a chance to become a real adult, in other words. 😍)

But by the time you are fully baked as a senior contributor, maybe 7-8 years in, your relationship to levels and ladders should undergo a dramatic shift. At some point you have to learn to tune in to your own inner compass. What draws you in to your work? What fuels your growth and success?

Being an adult means not measuring yourself entirely on other people’s definition of success. Personal growth might come in the guise of a big promotion, but it also might look like a new job, a different role, a swing to management or back, becoming well-known as a subject matter expert, mentoring others, running an affinity group, picking up new skill sets, starting a company, trying your hand at consulting, speaking at conferences, taking a sabbatical, having a family, working part time, etc. No one gets to define that but you.

You have a thirty- or forty-year adult life and career in front of you. What the hell are you going to do with all that time and space??

Your career is not one mad sprint to the finish line

Literally nobody’s career looks like a straight line, going up, up up and to the right, from intern to CEO (to a coffin).

One of the most exhausting things about working at Facebook was the way engineering levels felt like a hamster wheel, where every single quarter you were expected to go go go go go, do more do more, scrape up ever more of your mortal soul to pour in more than you could last quarter — and the quarter before that, and before that, in ever-escalating intensity.

like a hamster wheel, where every single quarter you were expected to go go go go go, do more do more, scrape up ever more of your mortal soul to pour in more than you could last quarter — and the quarter before that, and before that, in ever-escalating intensity.

It was fucking exhausting, yo. Life does not work that way. Shit gets hilly.

The strategy for a fulfilling, lifelong career in tech is not to up the ante every interval. Nor is it to amass more and more power over others until you explode. Instead:

- Train yourself to love the feeling of constantly learning and pushing your boundaries. Feeling comfortable is the system blinking orange, and it should make you uneasy.

- Follow your nose into work that lights you up in the morning, work you can’t stop thinking about. If you’re bored, do something else.

- Say yes to opportunities!! Intensity is nothing to be afraid of. Instead of trying to cap your speed or your growth, learn to alternate it with recovery periods.

- If you aren’t sure what to do, make the choice that preserves or expands future optionality. Remember: Most startups fail. Will you be okay with your choices if (& when) this one does too?

Why do people climb the ladder? “Because it’s there.” And when they don’t have any other animating goals, the ladder fills a vacuum.

But if you never make the leap from externally-motivated to intrinsically-motivated, this will eventually becomes a serious risk factor for your career. Without an inner compass (and a renewable source of joy), you will struggle to locate and connect with the work that gives your life meaning. You will risk burnout, apathy and a serious lack of fucks given..

The times I have come closest to burnout or flaming out have never been when I was working the hardest, but when I cared the least. Or when I felt the least needed.📈📉💔

A disturbing number of companies would rather feel in control than unclench and perform better

But hey! Lack of inner drive isn’t the ONLY thing that drives people to climb the ladder. Plenty of companies fuck this up too, all on their lonesome. Let’s talk about more of the ways that companies mess up the workplace! Like by disempowering the people doing the work and giving all the power to managers, thereby forcing anyone who wants a say in their own job become one.

The way we talk about work is riddled with hierarchical, authoritarian phrases: “She was my superior”, “My boss made me do it”, “I got promoted into management”, and so on.

There are plenty of industries where line workers are still disempowered cogs and power structures are hierarchical and absolute (like flipping burgers at McDonalds, or factory line work). There are even software companies still trying to make it work in command-and-control mode, to whom engineers are interchangeable monkeys that ship story points and close JIRA tasks.

structures are hierarchical and absolute (like flipping burgers at McDonalds, or factory line work). There are even software companies still trying to make it work in command-and-control mode, to whom engineers are interchangeable monkeys that ship story points and close JIRA tasks.

But if there’s one thing we know, it’s that for industries that are fueled by creativity and innovation, command-and-control leadership is poison. It stifles innovation, it saps initiative, it siphons away creativity and motivation and caring.

Studies also show that the more visible someone’s power is, the less likely anyone is to give them honest feedback.[2]

Companies that don’t learn this lesson are unlikely to win over the long run. Engineering is a deeply creative occupation, and authoritarian environments are toxic for creativity and people’s willingness to share information.

Hierarchy is just a data structure

The basic function of a hierarchy is to help us make sense of the world, simplify information, and make decisions. Hierarchy lets us break down enormous projects — like “let’s build a rocket!”, or “let’s invade the moon!” — into millions of bite size decisions and tasks, and this is how progress gets made.

A certain amount of authority is invested into the hierarchy model. If you are responsible for delivering a unit of work, the company needs to make sure you have enough resources and decision-making ability to do so. This is what we think of as the formal power structure [1], and there is nothing wrong with that. It’s what makes the system work.

The problem starts when we stop thinking of hierarchy as a neutral data structure — a utilitarian device for organizing groups and making decisions — and start projecting all kinds of social status and dominance onto it.

A sensitivity to social dominance is wired deep, deep into our little monkey brains. It’s what tells us we deserve more power, leverage, pride, influence, and autonomy — and simply have more value — than those below us. It’s what tells us those above us are better, stronger and more deserving than we are, and that we owe them our respect and deference.

It also tells us “if you lose status, YOU MIGHT DIE” 😱😱😱 which is why we may react to a perceived loss of status with a sting that seems astonishingly extreme and overwrought, even to ourselves, yet somehow impossible to shrug off.

hierarchies tend to get mixed up with social dominance

In general, it is better to pursue roles and growth based on the affirmative (what it is you want to learn, grow or do more of) than the negative (what you want to avoid, evade or stop doing). Your motivation systems don’t kick in to gear when you are feeling “lack of pain” — the system doesn’t work that way. They kick in when you get interested.

And if you are sick of doing something or being treated a certain way, chances are everyone else will hate it, too. Who wants to work at a company where all the shit rolls downhill?

And if you are sick of doing something or being treated a certain way, chances are everyone else will hate it, too. Who wants to work at a company where all the shit rolls downhill?

Hierarchies have stuck around for one very good reason: because they work. Hierarchies are simple, intuitive, and allow large numbers to collaborate with low cognitive overhead. Unfortunately, most hierarchies become entwined with status and dominance markers, which can bring enormous downsides. At their worst, they can suck the literal life out of work, reducing us all to glum little cogs obeying orders.

We aren’t getting rid of hierarchy anytime soon. But we can use culture and ritual to gently untangle them from dominance, and we can choose to interpret formal power as a service function instead of a dictatorship. This frees people up to choose their work based on what makes them feel fulfilled, instead of their perceived status. (Also helpful? Flatter pay bands. 😛)

Good managers do not dictate and demand, they nurture, develop, and inspire. The most important roles in the company aren’t held by managers; they are all the little leaf nodes busily building the product, supporting users, identifying markets, writing copy, etc. The people doing the work are why we exist as a company; all the rest is, with considerable due respect, overhead.

How to drain your hierarchy of social dominance

When it comes to hierarchy and team structure, there are the functional, organizational aspects (mostly good) and the social dominance parts (mostly bad). With that in mind, there are plenty of smaller things we can do as a team to remind people that we are equal colleagues, simply with different roles.

colleagues, simply with different roles.

- Be conscious of the language you use. Does it reinforce dominance and hierarchy? (Step one: stop calling management “a promotion”🥰)

- De-emphasize trappings of power. The more you refer to someone’s formal power, the less likely anyone is to give them critical feedback or question them.

- Push back against common but unhelpful practices, like “a manager should always make more money than the people who report to them.” Really? Why??

- Are there opportunities for career advancement as an IC, or only as a manager? Everyone should have the ability to advance in their career.

- Do your own dishes, everyone.

- Practice visualizing the org chart upside down, where managers and execs support their teams from below rather than topping them from above. (I was going to write a whole post about this, then discovered other people have been doing that for the past decade. 🤣)

And then there is the big(ger) thing we can (and must!) do, in order to 1) make people go into management for the right reasons, 2) help senior IC roles remain attractive to highly skilled creative and technical contributors, and 3) encourage everybody to make career decisions based on curiosity, growth, and what’s best for the business, instead of turf and power grabs. Which is:

Practice transparency, from top to bottom

Share authority, decision-making and power

Technical contributors own technical decisions

Most people who go in to management don’t do it out of a burning desire to write performance reviews. They do it because they are fed the fuck up with being out of the loop, or not having a say in decisions over their own work. All they want is to be in the room where it happens, and management tends to be the only way you get an invite.

EVERY company says they believe in transparency, but hardly any of them are, by my count. Transparency doesn’t mean flooding people with every trivial detail, or freaking them out with constant fire drills. It does mean being actively forthcoming about important questions and matters which are happening or on the horizon…often before you are fully comfortable with it. Honestly, if you never feel any discomfort about your level of transparency, you probably aren’t transparent enough.

People do better work with more context! You’re equipping them with information to better understand the business problems and technical objectives, and thereby unleashing them and their creativity to help solve them. You’re also opening yourself up to questioning and sanity checks — which may feel uncomfortable, but 🌞sunlight is sanitizing🌞 — it is worth it.

Some practical tips for transparency

At Honeycomb, we present the full board deck after every board meeting in our all hands, and take questions. When we’re facing financial uncertainty, we say so, along with our working plan for dealing with it. We also do org-level updates in all hands, once per quarter per org. Each org presents a snapshot to the company of how they are doing, but we ask that no more than 2/3 of the presentation be about their successes and triumphs, and 1/3 of their material be about their failures and misses. Normalize talking about failure.

Being transparent isn’t about putting everyone on blast; it’s about cultivating a habit of awareness about what might be relevant to other people. It’s about  building systems of feedback, updates and open questioning into your culture. This can be scary, so it’s also about training yourselves as a team to handle hard news without overreacting or shooting the messenger. If you always tell people what they want to hear, they’ll never trust you. You can’t trust someone’s ‘yes’ until you hear their ‘no’.

building systems of feedback, updates and open questioning into your culture. This can be scary, so it’s also about training yourselves as a team to handle hard news without overreacting or shooting the messenger. If you always tell people what they want to hear, they’ll never trust you. You can’t trust someone’s ‘yes’ until you hear their ‘no’.

Transparency is always a balance between information and distraction, but I think these are healthy internal rules of thumb for management:

- If anyone has further questions or wants to know more details than what was shared, they are free to ask any manager or exec, who will willingly answer more fully, up to the boundaries of privacy or legal reasons. As employees, they have a right to know about the business they are part of. A right — not a privilege, which can be revoked on a whim.

- When making internal decisions about e.g. salary bands, individual exceptions to formal policy, etc, ask each other … if this decision were to leak, could we justify our reasoning with head held high? If you would feel ashamed, or if you really don’t want people to find out about it, it’s probably the wrong decision.

Some practical tips for distributing power

Power flows to managers by default, just like water flows downhill. Managers have to actively push back on this tendency by explicitly allocating powers and responsibilities to tech leads and engineers. Don’t hoard information, share context generously, and make sure you know when they would want to tap in to a discussion. Your job is not to “shield” them from the rest of the org; your job is to help them determine where they can add outsize value, and include them. Only if they trust you to loop them in will they feel free to go heads down and focus.

Wrap your senior ICs into planning and other leadership activities. Decisions about sociotechnical processes (code reviews, escalation points, SLI/SLOs, ownership etc) are usually better owned by staff+ engineers than anyone on the management track. Invite a couple of your seniormost engineers to join calibrations — they bring a valuable perspective to performance discussions that managers lack.

Demystify management. Blur the lines between people managers and engineers; delegate ownership and accountability for some important projects to ICs. Ask every engineer about their career interests, and if management is on the list, find opportunities for them to practice and improve at managerial skills — mentoring, interviewing, onboarding, etc.

Adults don’t like being told what to do

People do phenomenal work when they want to do it, when they are creatively and emotionally engaged at the level of optimum challenge, and when they know their work matters. That’s where you’ll find your state of flow. That is where you’ll do your best work, which is also the best way to get promoted and make durable advances in your career.

Not, ironically, by chasing levels and titles for their own sake. ☺️

People want to be challenged. They want you to ask them to step up and take responsibility for something hard. They want to be needed, and they want to have agency in the doing of it. Just like you do.

Oh yeah, back to Molly …

Molly, who I mentioned at the beginning, joined Honeycomb five years ago as a customer success exec. After realizing she wanted to go back to engineering, she switched to working our support desk to build up her technical chops while she practiced writing code on the side. She has now been working as a software engineer on the product team for over two years, and she is ✨rocking it.✨ It is NEVER too late. 🙌

working as a software engineer on the product team for over two years, and she is ✨rocking it.✨ It is NEVER too late. 🙌

<3 charity

p.s. Molly also says, “don’t waste time at bad companies, whether you’re climbing the ladder or not!” 🥂

[1] Formal power is only one kind of power, and in some ways it is the weakest, because it doesn’t belong to you. It belongs to the company and is only loaned out for you to wield on its behalf. (You don’t carry the innate ability to fire people along with you after you stop being an engineering manager, for example.) Formal powers are limited, enumerated, and functional. You don’t get to use them for any reason other than furthering the goals of the org, or else it is literally an abuse of power.

Formal power is fascinating in another way, too: which is that your formal power is seen as legitimate only if you ~basically always wield it in the ways everyone already expects you to. You can make a surprising call only so often; you can straight up overrule the wishes of your constituents extremely rarely. If you use your formal power to do things that people disagree with or don’t support, without taking the time to persuade them or create real consensus, you will squander your credibility and good faith unbelievably fast.

[2] I am not going to bother rustling up lots of links and citations, because I expect most of this falls into the voluminous category of “shit you already knew”. But if any of it sounds surprising to you, here are some classic reference works:

Flow, by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Drive, by Dan Pink

The Culture Code: Secrets of Successful Groups, by Daniel Coyle

A Lapsed Anarchist’s Guide to Being a Better Leader, by Ari Weinzweig

[3] The scientific literature suggests that dominating instincts tend to emerge in more overtly hostile environments. Make of that what you will, I guess.

Some other writing I have done on this topic, or topics adjacent …

The Engineer/Manager Pendulum

The Pendulum or the Ladder

If Management Isn’t a Promotion, then Engineering isn’t a Demotion

Twin Anxieties of the Engineer Manager Pendulum

Things to Know About Engineering Levels

Advice for Engineering Managers who want to Climb the Ladder

On Engineers and Influence

Is There a Path Back from CTO to Engineer?

approval. The early years of professional life are a similar blend of hard work, leveling up and basic skills acquisition. (They got Molly hopped on the leveling treadmill before she even had a chance to become a real adult, in other words. 😍)

approval. The early years of professional life are a similar blend of hard work, leveling up and basic skills acquisition. (They got Molly hopped on the leveling treadmill before she even had a chance to become a real adult, in other words. 😍) like a hamster wheel, where every single quarter you were expected to go go go go go, do more do more, scrape up ever more of your mortal soul to pour in more than you could last quarter — and the quarter before that, and before that, in ever-escalating intensity.

like a hamster wheel, where every single quarter you were expected to go go go go go, do more do more, scrape up ever more of your mortal soul to pour in more than you could last quarter — and the quarter before that, and before that, in ever-escalating intensity. structures are hierarchical and absolute (like flipping burgers at McDonalds, or factory line work). There are even software companies still trying to make it work in command-and-control mode, to whom engineers are interchangeable monkeys that ship story points and close JIRA tasks.

structures are hierarchical and absolute (like flipping burgers at McDonalds, or factory line work). There are even software companies still trying to make it work in command-and-control mode, to whom engineers are interchangeable monkeys that ship story points and close JIRA tasks. And if you are sick of doing something or being treated a certain way, chances are everyone else will hate it, too. Who wants to work at a company where all the shit rolls downhill?

And if you are sick of doing something or being treated a certain way, chances are everyone else will hate it, too. Who wants to work at a company where all the shit rolls downhill? colleagues, simply with different roles.

colleagues, simply with different roles. building systems of feedback, updates and open questioning into your culture. This can be scary, so it’s also about training yourselves as a team to handle hard news without overreacting or shooting the messenger. If you always tell people what they want to hear, they’ll never trust you. You can’t trust someone’s ‘yes’ until you hear their ‘no’.

building systems of feedback, updates and open questioning into your culture. This can be scary, so it’s also about training yourselves as a team to handle hard news without overreacting or shooting the messenger. If you always tell people what they want to hear, they’ll never trust you. You can’t trust someone’s ‘yes’ until you hear their ‘no’. working as a software engineer on the product team for over two years, and she is ✨rocking it.✨ It is NEVER too late. 🙌

working as a software engineer on the product team for over two years, and she is ✨rocking it.✨ It is NEVER too late. 🙌 physical with the psychological and emotional, all with the benefit of “regulation” and intentionality. Physically going through the process of a ritual helps people feel satisfied and in control, with better emotional regulation and the ability to act in a steadier and more focused way. Rituals also powerfully increase people’s sense of belonging, giving them a stable feeling of social connection. (p. 5-6)

physical with the psychological and emotional, all with the benefit of “regulation” and intentionality. Physically going through the process of a ritual helps people feel satisfied and in control, with better emotional regulation and the ability to act in a steadier and more focused way. Rituals also powerfully increase people’s sense of belonging, giving them a stable feeling of social connection. (p. 5-6)

hands. (It was a very sparkly rhinestone wedding tiara, and every engineer looked simply gorgeous in it.)

hands. (It was a very sparkly rhinestone wedding tiara, and every engineer looked simply gorgeous in it.)

providing biweekly updates to the infra leadership groups. Four months later, when the migration was half done, I get a ping from the same exact members of Facebook leadership:

providing biweekly updates to the infra leadership groups. Four months later, when the migration was half done, I get a ping from the same exact members of Facebook leadership:

prove that I shaved the heads of and/or dyed the hair blue of at least seven members of engineering. I wish I could remember why! but all I remember is that it was fucking hilarious.

prove that I shaved the heads of and/or dyed the hair blue of at least seven members of engineering. I wish I could remember why! but all I remember is that it was fucking hilarious.

In brief: if you aren’t rolling out a solution based on arbitrarily wide, structured raw events that are unique and ordered and trace-aware and without any aggregation at write time, you are going to regret it. (If you aren’t using OpenTelemetry, you are going to regret that, too.)

In brief: if you aren’t rolling out a solution based on arbitrarily wide, structured raw events that are unique and ordered and trace-aware and without any aggregation at write time, you are going to regret it. (If you aren’t using OpenTelemetry, you are going to regret that, too.) unknown-unknowns. Which requires a fundamentally different mindset and toolchain.

unknown-unknowns. Which requires a fundamentally different mindset and toolchain. Observability is often about swiftly isolating or tracking down the problem in your large, sprawling, far-flung, dynamic system. Because the hard part of distributed systems is rarely debugging the code, it’s figuring out where the code you need to debug is.

Observability is often about swiftly isolating or tracking down the problem in your large, sprawling, far-flung, dynamic system. Because the hard part of distributed systems is rarely debugging the code, it’s figuring out where the code you need to debug is.

your system without shipping new code, and aggregation is a one-way trip. Once you have aggregated your data and discarded the raw requests, you have destroyed your ability to ask new questions of that data forever. For Ever.

your system without shipping new code, and aggregation is a one-way trip. Once you have aggregated your data and discarded the raw requests, you have destroyed your ability to ask new questions of that data forever. For Ever.

design review, which means you have to redo some components you thought were finished. It’s a considerable amount of work, and this isn’t the first (or second) time, either. You want to tell them so and try to debug this so it doesn’t keep happening.

design review, which means you have to redo some components you thought were finished. It’s a considerable amount of work, and this isn’t the first (or second) time, either. You want to tell them so and try to debug this so it doesn’t keep happening. messaging frameworks in general are used. I understand its impact on my role better now than I have in seven years of product marketing!”

messaging frameworks in general are used. I understand its impact on my role better now than I have in seven years of product marketing!” As a former CTO, you have many other skill sets to pull from — management, strategy, architecture, coaching, staffing, fundraising, etc. These skills are valuable. But they don’t degrade the way hands-on development does. You’ll still remember how to write a performance review two (or twenty) years from now, but writing code is like speaking a language: you use it or lose it. And just like with a language, the best way to freshen up is full immersion.

As a former CTO, you have many other skill sets to pull from — management, strategy, architecture, coaching, staffing, fundraising, etc. These skills are valuable. But they don’t degrade the way hands-on development does. You’ll still remember how to write a performance review two (or twenty) years from now, but writing code is like speaking a language: you use it or lose it. And just like with a language, the best way to freshen up is full immersion. that you have to allow enough time to become a different version of yourself. You can’t just change personas and entire ways of being like you change your clothing. The process is more like…a snake shedding its skin, or a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. Don’t rush the process.

that you have to allow enough time to become a different version of yourself. You can’t just change personas and entire ways of being like you change your clothing. The process is more like…a snake shedding its skin, or a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. Don’t rush the process. And you better fucking love it, if you plan to inflict the world of agonies that is software development on yourself day after day. 😭 So you have to reconnect with that dopamine drip you get from learning things, fixing shit, and solving problems. And you have to reconnect with the emotional intensity of shipping code that will impact people’s lives — for better or for worse — and of being personally responsible for that code in production. Of knowing viscerally what it’s like to ship a diff that brings production down, or wakes up your coworker in the middle of the night, or corrupts user data.

And you better fucking love it, if you plan to inflict the world of agonies that is software development on yourself day after day. 😭 So you have to reconnect with that dopamine drip you get from learning things, fixing shit, and solving problems. And you have to reconnect with the emotional intensity of shipping code that will impact people’s lives — for better or for worse — and of being personally responsible for that code in production. Of knowing viscerally what it’s like to ship a diff that brings production down, or wakes up your coworker in the middle of the night, or corrupts user data. staff+ engineer once you’ve done the refreshing.

staff+ engineer once you’ve done the refreshing.

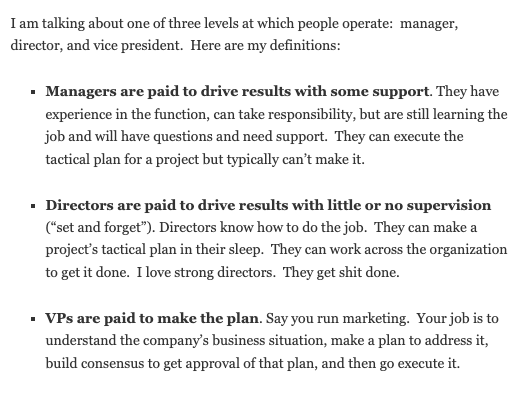

engineering director manages 2-5 engineering managers, and a VP of engineering manages the directors. (At big companies, you may see managers and directors reporting to other managers and directors, and/or you may find a bunch of ‘title padding’ roles like Senior Manager, Senior Director etc.)

engineering director manages 2-5 engineering managers, and a VP of engineering manages the directors. (At big companies, you may see managers and directors reporting to other managers and directors, and/or you may find a bunch of ‘title padding’ roles like Senior Manager, Senior Director etc.) When you are internally promoted, you already know the company and the people, so you get a leg up towards being successful. Whereas if you’ve just joined the company and are trying to learn the tech, the people, the relationships, and how the company works all at once, on top of trying to perform a new role for the first time.. well, that is a lot to take on at once.

When you are internally promoted, you already know the company and the people, so you get a leg up towards being successful. Whereas if you’ve just joined the company and are trying to learn the tech, the people, the relationships, and how the company works all at once, on top of trying to perform a new role for the first time.. well, that is a lot to take on at once. usually get surprise-dropped on people’s heads; people are usually cultivated for them. Registering your interest makes it more likely they will consider you, or help you develop skills in that direction as time moves on.

usually get surprise-dropped on people’s heads; people are usually cultivated for them. Registering your interest makes it more likely they will consider you, or help you develop skills in that direction as time moves on. If you do need to find a new job to reach your career goals, I would target fast-growing companies with at least 100 engineers. If you’re evaluating prospective employers based on your chance of advancement, consider the following::

If you do need to find a new job to reach your career goals, I would target fast-growing companies with at least 100 engineers. If you’re evaluating prospective employers based on your chance of advancement, consider the following:: while directors absolutely must balance lots of different stakeholders to achieve healthy business outcomes.

while directors absolutely must balance lots of different stakeholders to achieve healthy business outcomes.

overheard fragments of people talking about you…even the expressions on your face as they pass you in the hallway. People will extrapolate a lot from a very little, and changing their impression of you later is hard work.

overheard fragments of people talking about you…even the expressions on your face as they pass you in the hallway. People will extrapolate a lot from a very little, and changing their impression of you later is hard work. listening closely to how they talk about their colleagues. Do they complain about being misunderstood or mistreated, do they minimize the difficulty or quality of others’ work, do they humblebrag, or do they take full responsibility for outcomes? And does their empathy fully extend to their peers in other departments, like sales and marketing?

listening closely to how they talk about their colleagues. Do they complain about being misunderstood or mistreated, do they minimize the difficulty or quality of others’ work, do they humblebrag, or do they take full responsibility for outcomes? And does their empathy fully extend to their peers in other departments, like sales and marketing?

I received this question in the comments section of my piece on The Twin Anxieties of the Engineer/Manager Pendulum, and figured I might as well answer it. It definitely isn’t a question I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about or anything. 🥰