Original title: “Why Should You (Or Anyone) Become An Engineering Manager?”

The first piece I ever wrote about engineering management, The Engineer/Manager Pendulum, was written as a love letter to a friend of mine who was unhappy at work. He was an engineering director at a large and fast-growing startup, where he had substantially built out the entire infrastructure org, but he really missed being an engineer and building things. He wasn’t getting a lot of satisfaction out of his work, and he felt like there were other people who might relish the challenge and do it better than he could.

At the same time, it felt like a lot to walk away from! He had spent years building up not only the teams, but also his influence and reputation. He had grown accustomed to being in the room where decisions get made, and didn’t want to give that up or take a big step back in his career. He agonized over this for a long time (and I listened over many whiskeys). 🙂

To me it seemed obvious that his power and influence would only increase if he went back to engineering. You bring your credibility and your relationships along with you, and enthusiasm is contagious. So I wrote the piece with him in mind, but it definitely struck a nerve; it is still the most-read piece I have ever written.

That was in 2017. I’ve written a lot over the years since then about teams and management. For a long time, everything I wrote seemed to come out with a pretty noticeable bias against management, towards engineering:

- 17 Reasons NOT To Be A Manager

- On Engineers and Influence (aka how to wield influence as an IC)

- An Engineer’s Bill of Rights (and Responsibilities)

- A Manager’s Bill of Responsibilities (and Rights)

- The Official, Authorized List of Legitimate Reasons for Becoming a Manager

- After Being A Manager, Can I Still Be Happy As A Cog?

- How To Drive Teams and Influence Teams Without Power

- Is There A Path Back From CTO To Engineer?

- If Management Isn’t A Promotion, Then Engineering Isn’t A Demotion

I go back and read some of those pieces now, and the pervasive anti-manager slant actually makes me a bit uncomfortable, because the environment has changed quite a lot since then.

Miserable managers have miserable reports

When I started writing about engineering management, it seemed like there were a lot of unhappy, resentful, poorly trained managers, lots of whom would prefer to be writing code. Most people made the choice to switch to management for reasons that had nothing to do with the work itself.

- Becoming a manager was seen as a promotion

- It was the only form of career progression available at many places

- Managers made a lot more money

- It was the only way to get a seat at the table, or be in the loop

- They were tired of taking orders from someone else

But a lot has changed. The emergence of staff+ engineering has been huge (two new books published in the last five years, and at least one conference!). The industry has broadly coalesced around engineering levels and career progression; a parallel technical leadership track is now commonplace.

We’ve become more aware of how fragile command-and-control systems are, and that you want to engage people’s agency and critical thinking skills. You want them to feel ownership over their labor. You can’t build great software on autopilot, or by picking up jira tasks. Our systems are becoming so complex that you need people to be emotionally and mentally engaged, curious, and continuously learning and improving, both as individuals and as teams.

I tell people all the time that you can do most of the "fun" management things (mentoring, coaching, watching people grow, contributing to decision making) as an IC without doing all the terrible parts of management (firing, budgeting, serious HR things).

— Jill Wetzler (@JillWetzler) September 5, 2019

At the same time, our expectations for managers have gone up dramatically. We’ve become more aware of the damage done by shoddy managers, and we increasingly expect managers to be empathetic, supportive, as well as deeply technical. All of this has made the job of engineering manager more challenging.

Ambitious engineers had already begun to drift away from management and towards the role of staff or principal engineer. And then came the pandemic, which caused managers (poorly supported, overwhelmed, squeezed between unrealistic expectations on both sides) to flee the profession in droves.

It’s getting harder to find people who are willing to be managers. On the one hand, it is fucking fantastic that people aren’t being driven into management out of greed, rage, or a lust for power. It is WONDERFUL that people are finding engineering roles where they have autonomy, ownership, and career progression, and where they are recognized and rewarded for their contributions.

On the other hand, engineering managers are incredibly important and we need them. Desperately.

Good engineering managers are force multipliers

A team with a good engineering manager will build circles around a team without one. The larger or more complex the org or the product, and the faster you want to move, the more true this is. Everybody understands the emotional component, that it feels nice to have a competent manager you trust. But these aren’t just squishy feels. This shit translates directly into velocity and quality. The biggest obstacles to engineering productivity are not writing lines of code too slowly or not working long hours, they are:

- Working on the wrong thing

- Getting bogged down in arguments, or being endlessly indecisive

- Waiting on other teams to do their work, waiting on code review

- Ramping new engineers, or trying to support unfamiliar code

- When people are upset, distracted, or unmotivated

- Unfinished migrations, migrations in flight, or having to support multiple systems indefinitely

- When production systems are poorly understood and opaque, quality suffers, and firefighting skyrockets

- Terrible processes, tools, or calendars that don’t support focus time

- People who refuse to talk to each other

- Letting bad hires and chronic underperformers stick around indefinitely

Engineers are responsible for delivering products and outcomes, but managers are responsible for the systems and structural support that enables this to happen.

Managers don’t make all the decisions, but they do ensure the decisions get made. They make sure that workstreams are are staffed and resourced sufficiently, that engineers are trained and improving at their craft. They pay attention to the contracts and commitments you have made with other teams, companies or orgs. They advocate for your needs at all levels of the organization. They connect dots and nudge and suggest ideas or solutions, they connect strategy with execution.

Breaking down a complex business problem into a software project that involves the collaboration of multiple teams, and ensuring that every single contributor has work to do that is challenging and pushes their boundaries while not being overwhelming or impossible… is really fucking hard. Even the best leaders don’t get it right every time.

In systems theory, hierarchy emerges for the benefit of the subsystems. Hierarchy exists to coordinate between the subsystems and help them improve their function; it is how systems create resiliency to unknown stressors. Which means that managers are, in a very real way, the embodiment of the feedback loops and meta loops that a system depends on to align itself and all of its parts around a goal, and for the system itself to improve over time.

For some people, that is motivation enough to try being a manager. But not for all (and that’s okay!!). What are some other reasons for going into management?

Why should you (or anyone) be a manager?

I can think of a few good reasons off the top of my head, like…

- It gets you closer to how the business operates, and gives you a view into how and why decisions get made that translate eventually into the work you do as an engineer

- Which makes the work feel more meaningful and less arbitrary, I think. It connects you to the real value you are creating in the world.

- Many people reach a point where they feel a gravitational pull towards mentorship. It’s almost like a biological imperative to replicate yourself and pass on what you have learned to the next generation.

- Many people also get to a point where they develop strong convictions about what not to do as a manager. They may feel compelled to use what they’ve learned to build happy teams and propagate better practices through the industry

- One way to develop a great staff engineer is to take a great senior engineer and put them through 2-3 years of management experience.

But the main reason I would encourage you to try engineering management is a reason that I’m not sure I’ve ever heard someone articulate up front, which is that…it can make you better at life and relationships, in a huge and meaningful way.

Work is always about two things: what you put out into the world, and who you become while doing it.

I want to stop short of proclaiming that “being a manager will make you a better person!” — because skills are skills, and they can be used for good or ill. But it can.

It’s a lot like choosing to become a parent. You don’t decide to have kids because it sounds like a hoot (I hope); you go into it knowing it will be hard work, but meaningful work. It’s a way of processing and passing on the experiences that have shaped you and who you are. You also take up the mantle understanding that this will change you — it changes who you are as a person, and the relationships you have with others.

From the outside, management looks like making decisions and calling the shots. From the inside, management looks more like becoming intimately acquainted with your own limitations and motivations and those of others, plus a lot of systems thinking.

Yes, management absolutely draws on higher-level skills like strategy and planning, writing reviews, mediating conflict, designing org charts, etc. But being a good manager — showing up for other people and supporting them consistently, day after day — rests on a bedrock of some much more foundational skills.

The kind of skills you learn in therapy, not in classes

Self-regulation. Can you take care of yourself consistently — sleep, eat, leave the house, socialize, balance your moods, moderate your impulses? As an engineer, you can run your tank dry on occasion, but as a manager, that’s malpractice. You always need to have fuel left in the tank, because you don’t know when it will be called upon.

Self-awareness. Identifying your feelings in the heat of the moment, unpacking where they came from, and deciding how to act on them. It’s not about clamping down on your feelings and denying you have them. It’s definitely not about making your feelings into other people’s problems, or letting your reactions create even bigger problems for your future self. It’s about acting in ways that are fueled by your authentic emotional responses, but not ruled by them.

Understanding other people. You learn to read people and their reactions, starting with your direct reports. You build up a mental model for what motivates someone, what moves them, what bothers them, and what will be extremely challenging for them. You must develop a complex topographical map of how much you can trust each person’s judgment, on which aspect, in any given situation.

Setting good boundaries. Where is the line between supporting someone, advocating for them, encouraging them, pushing them … but not propping them up at all costs, or taking responsibility for their success? How is the manager/report relationship different from the coworker relationship, or the friend relationship? How do you navigate the times when you have to hold someone accountable because their work is falling short?

Sensitivity to power dynamics. Do people treat you differently as a manager than they did as a peer? Are there things that used to be okay for you to say or do that now come across as inappropriate or coercive? How does interacting with your reports inform the way you interact with your own manager, or how you understand what they say?

Hard conversations. Telling people things that you know they don’t want to hear, or things that will make them feel afraid, angry, or upset; and then sitting with their reactions, resisting the urge to take it all back and make everything okay.

The art of being on the same side. When you’re giving someone feedback, especially constructive feedback, it’s easy to trigger a defensive response. It’s SO easy for people to feel like you are judging them or criticizing them. But the dynamic you want to foster is one where you are both side by side, shoulder to shoulder, facing the same way, working together. You are giving them feedback because you care; feedback that could help them be even better, if they choose to accept it. You are on their side. They always have agency.

Did you learn these skills growing up? I sure as hell did not.

I grew up in a family that was very nice. It was very kind and loving and peaceful, but we did not tell each other hard things. When I went off to college and started dating, I had no idea how to speak up when something bothered me. There were sentences that lingered on the tip of my tongue for years but were never spoken out loud, over the ebb and fall of entire relationships. And if somebody raises their voice to me in anger, to this day, I crumble.

I also came painfully late to developing a so-called growth mindset. This is super common among “smart kids”, who get so used to perfect scores and praise for high achievements that any feedback or critique feels like failure…and failure feels like the end of the world.

It was only after I became a manager that I began to consciously practice skills like giving feedback, or receiving constructive criticism, or initiating hard conversations. I had to. But once I did, I started getting better.

Turns out, work is actually kind of an ideal sandbox for life skills, because the social contract is more explicit. These are structured relationships, with rules and conventions and expectations, and your purpose for coming together is clear: to succeed at business, to finish a project, to pull a paycheck. Even the element of depersonalization can be useful: it’s not you-you, it’s the professional version of you, performing a professional role. The stakes are lower than they would be with your mother, your partner, or your child.

You don’t have to be a manager to build these skills, of course. But it’s a great opportunity to do so! And there are tools — books and classes, mentors and review cycles. You can ask for feedback from others. Growth and development is expected in this role.

People skills are persistent

The last thing I will say is this — technical skills do decay and become obsolete, particularly language fluency, but people skills do not. Once you have built these muscles, you will carry them with you for life. They will enhance your ability to connect with people and build trust, to listen perceptively and communicate clearly, in both personal and professional relationships.

Whatever you decide to do with your life, these skills increase your optionality and make you more effective.

And that is the reason I think you should consider being an engineering manager. Like I said, I’ve never heard someone cite this as their reason for wanting to become a manager. But if you ask managers why they do it five or ten years later, you hear a version of this over and over again.

One cautionary note

As an engineer, you can work for a company whose leadership team you don’t particularly respect, whose product you don’t especially love, or whose goals you aren’t super aligned with, and it can be “okay.” Not terrific, but not terrible.

As a manager, you can’t. Or you shouldn’t. The conflicts will eat you up inside and/or prevent you from doing excellent work.

Your job consists of representing the leadership team and their decisions, pulling people into alignment with the company’s goals, and thinking about how to better achieve the mission. As far as your team goes, you are the face of The Man. If you can’t do that, you can’t do your job. You don’t get to stand apart from the org and throw rocks, e.g. “they told me I have to tell you this, but I don’t agree with it”. That does nothing but undermine your own position and the company’s. If you’re going to be a manager, choose your company wisely.

charity

P.S. My friend (from the start of the article) went back to being an engineer, despite his trepidation, and never regretted it once. His career has been up and to the right ever since; he went on to start a company. The skills he built as a manager were a huge boost to an already stellar career. 📈

approval. The early years of professional life are a similar blend of hard work, leveling up and basic skills acquisition. (They got Molly hopped on the leveling treadmill before she even had a chance to become a real adult, in other words. 😍)

approval. The early years of professional life are a similar blend of hard work, leveling up and basic skills acquisition. (They got Molly hopped on the leveling treadmill before she even had a chance to become a real adult, in other words. 😍) like a hamster wheel, where every single quarter you were expected to go go go go go, do more do more, scrape up ever more of your mortal soul to pour in more than you could last quarter — and the quarter before that, and before that, in ever-escalating intensity.

like a hamster wheel, where every single quarter you were expected to go go go go go, do more do more, scrape up ever more of your mortal soul to pour in more than you could last quarter — and the quarter before that, and before that, in ever-escalating intensity. structures are hierarchical and absolute (like flipping burgers at McDonalds, or factory line work). There are even software companies still trying to make it work in command-and-control mode, to whom engineers are interchangeable monkeys that ship story points and close JIRA tasks.

structures are hierarchical and absolute (like flipping burgers at McDonalds, or factory line work). There are even software companies still trying to make it work in command-and-control mode, to whom engineers are interchangeable monkeys that ship story points and close JIRA tasks. And if you are sick of doing something or being treated a certain way, chances are everyone else will hate it, too. Who wants to work at a company where all the shit rolls downhill?

And if you are sick of doing something or being treated a certain way, chances are everyone else will hate it, too. Who wants to work at a company where all the shit rolls downhill? colleagues, simply with different roles.

colleagues, simply with different roles. building systems of feedback, updates and open questioning into your culture. This can be scary, so it’s also about training yourselves as a team to handle hard news without overreacting or shooting the messenger. If you always tell people what they want to hear, they’ll never trust you. You can’t trust someone’s ‘yes’ until you hear their ‘no’.

building systems of feedback, updates and open questioning into your culture. This can be scary, so it’s also about training yourselves as a team to handle hard news without overreacting or shooting the messenger. If you always tell people what they want to hear, they’ll never trust you. You can’t trust someone’s ‘yes’ until you hear their ‘no’. working as a software engineer on the product team for over two years, and she is ✨rocking it.✨ It is NEVER too late. 🙌

working as a software engineer on the product team for over two years, and she is ✨rocking it.✨ It is NEVER too late. 🙌 design review, which means you have to redo some components you thought were finished. It’s a considerable amount of work, and this isn’t the first (or second) time, either. You want to tell them so and try to debug this so it doesn’t keep happening.

design review, which means you have to redo some components you thought were finished. It’s a considerable amount of work, and this isn’t the first (or second) time, either. You want to tell them so and try to debug this so it doesn’t keep happening. messaging frameworks in general are used. I understand its impact on my role better now than I have in seven years of product marketing!”

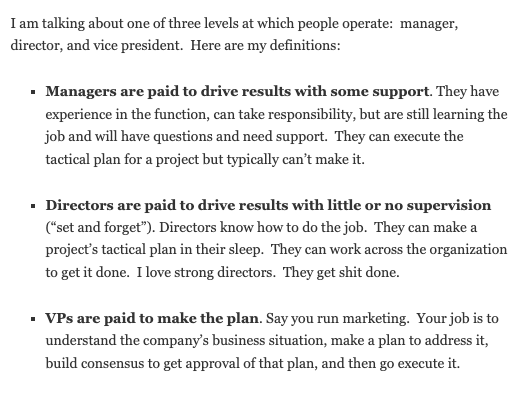

messaging frameworks in general are used. I understand its impact on my role better now than I have in seven years of product marketing!” engineering director manages 2-5 engineering managers, and a VP of engineering manages the directors. (At big companies, you may see managers and directors reporting to other managers and directors, and/or you may find a bunch of ‘title padding’ roles like Senior Manager, Senior Director etc.)

engineering director manages 2-5 engineering managers, and a VP of engineering manages the directors. (At big companies, you may see managers and directors reporting to other managers and directors, and/or you may find a bunch of ‘title padding’ roles like Senior Manager, Senior Director etc.) When you are internally promoted, you already know the company and the people, so you get a leg up towards being successful. Whereas if you’ve just joined the company and are trying to learn the tech, the people, the relationships, and how the company works all at once, on top of trying to perform a new role for the first time.. well, that is a lot to take on at once.

When you are internally promoted, you already know the company and the people, so you get a leg up towards being successful. Whereas if you’ve just joined the company and are trying to learn the tech, the people, the relationships, and how the company works all at once, on top of trying to perform a new role for the first time.. well, that is a lot to take on at once. usually get surprise-dropped on people’s heads; people are usually cultivated for them. Registering your interest makes it more likely they will consider you, or help you develop skills in that direction as time moves on.

usually get surprise-dropped on people’s heads; people are usually cultivated for them. Registering your interest makes it more likely they will consider you, or help you develop skills in that direction as time moves on. If you do need to find a new job to reach your career goals, I would target fast-growing companies with at least 100 engineers. If you’re evaluating prospective employers based on your chance of advancement, consider the following::

If you do need to find a new job to reach your career goals, I would target fast-growing companies with at least 100 engineers. If you’re evaluating prospective employers based on your chance of advancement, consider the following:: while directors absolutely must balance lots of different stakeholders to achieve healthy business outcomes.

while directors absolutely must balance lots of different stakeholders to achieve healthy business outcomes.

overheard fragments of people talking about you…even the expressions on your face as they pass you in the hallway. People will extrapolate a lot from a very little, and changing their impression of you later is hard work.

overheard fragments of people talking about you…even the expressions on your face as they pass you in the hallway. People will extrapolate a lot from a very little, and changing their impression of you later is hard work. listening closely to how they talk about their colleagues. Do they complain about being misunderstood or mistreated, do they minimize the difficulty or quality of others’ work, do they humblebrag, or do they take full responsibility for outcomes? And does their empathy fully extend to their peers in other departments, like sales and marketing?

listening closely to how they talk about their colleagues. Do they complain about being misunderstood or mistreated, do they minimize the difficulty or quality of others’ work, do they humblebrag, or do they take full responsibility for outcomes? And does their empathy fully extend to their peers in other departments, like sales and marketing?

As a senior software engineer, there are fifteen bajillion job openings for you. Everyone wants to hire you. You can get a new job in a matter of days, no matter how picky you want to be about location, flexibility, technologies, product types, whatever. You’ve reached Peak Hire.

As a senior software engineer, there are fifteen bajillion job openings for you. Everyone wants to hire you. You can get a new job in a matter of days, no matter how picky you want to be about location, flexibility, technologies, product types, whatever. You’ve reached Peak Hire.

a job where your core responsibilities are writing and speaking. I don’t know. All I know is that if I’m the manager of that team, my responsibility and loyalty is to the well-functioning of that team, so we need to have a conversation and clarify what’s happening.

a job where your core responsibilities are writing and speaking. I don’t know. All I know is that if I’m the manager of that team, my responsibility and loyalty is to the well-functioning of that team, so we need to have a conversation and clarify what’s happening. I cannot honestly understand why this is controversial. If you were hired as a database engineer, and you spent the year doing mostly DEI work, how does it make sense to promote you to the next level as a database engineer? That’s not setting you up for success at the next level at ALL. If this was agreed upon by you and your manager, I can see giving you glowing reviews for the period of time spent on DEI work, as long as your dbeng responsibilities were gracefully handed off to someone else (and not just dropped), but not promoting you for it.

I cannot honestly understand why this is controversial. If you were hired as a database engineer, and you spent the year doing mostly DEI work, how does it make sense to promote you to the next level as a database engineer? That’s not setting you up for success at the next level at ALL. If this was agreed upon by you and your manager, I can see giving you glowing reviews for the period of time spent on DEI work, as long as your dbeng responsibilities were gracefully handed off to someone else (and not just dropped), but not promoting you for it. negotiate a job that has a LOT of icing — but you should negotiate, no surprises. DEI work is absolutely valuable to companies, because having a diverse workforce is a competitive advantage and increasingly a hiring advantage. But that work isn’t typically budgeted under engineering, it comes from G&A

negotiate a job that has a LOT of icing — but you should negotiate, no surprises. DEI work is absolutely valuable to companies, because having a diverse workforce is a competitive advantage and increasingly a hiring advantage. But that work isn’t typically budgeted under engineering, it comes from G&A managers who were good at setting structure and boundaries, deeply encouraging, gave tons of chances and great constant feedback, tried every which way to make it work … and the employee just wasn’t interested. They volunteered for every social committee and followed every butterfly that fluttered by. They just weren’t into the work.

managers who were good at setting structure and boundaries, deeply encouraging, gave tons of chances and great constant feedback, tried every which way to make it work … and the employee just wasn’t interested. They volunteered for every social committee and followed every butterfly that fluttered by. They just weren’t into the work.

A surprising number of people thought I was writing this as advice specifically to and for women, and got mad about that. Nope, sorry. It was not a gendered thing at all. I’ve seen this happen pretty much equally with men and women. I had planned on writing three or four anecdotes, using multiple fake names and genders, but the first one turned out long so I stopped.

A surprising number of people thought I was writing this as advice specifically to and for women, and got mad about that. Nope, sorry. It was not a gendered thing at all. I’ve seen this happen pretty much equally with men and women. I had planned on writing three or four anecdotes, using multiple fake names and genders, but the first one turned out long so I stopped. that was less easy to nitpick. But I didn’t want anyone to see themselves in it, so I didn’t want it to be too recognizable or realistic. I just wanted a placeholder for “Person who does lots of great stuff at work”, and that’s how you got Susan.

that was less easy to nitpick. But I didn’t want anyone to see themselves in it, so I didn’t want it to be too recognizable or realistic. I just wanted a placeholder for “Person who does lots of great stuff at work”, and that’s how you got Susan. proposals… typical glue work. If you have a manager that thinks you are only doing your One Job when you are heads down writing code with your headphones on, that’s a Really Bad Manager.

proposals… typical glue work. If you have a manager that thinks you are only doing your One Job when you are heads down writing code with your headphones on, that’s a Really Bad Manager. their best for each other, with comparatively low levels of assholery, sociopaths, and other bad actors. If your situation is very unlike mine, I can understand why my advice could seem blinkered, naive, and even harmful. Please use your own judgment.

their best for each other, with comparatively low levels of assholery, sociopaths, and other bad actors. If your situation is very unlike mine, I can understand why my advice could seem blinkered, naive, and even harmful. Please use your own judgment.

situations.

situations.

Susan also runs three employee resource groups, mentors other women in tech both internally and external to the company, and spends a lot of time recruiting candidates to come work here. She never turns down a request to speak at a meetup or conference, and frequently writes blog posts, too. She is extremely responsive on chat, and answers all the questions her coworkers have when they pop into the team slack. Susan has a high profile in the community and her peer reviews are always sprinkled lavishly with compliments and rave reviews from cross-functional coworkers across the company.

Susan also runs three employee resource groups, mentors other women in tech both internally and external to the company, and spends a lot of time recruiting candidates to come work here. She never turns down a request to speak at a meetup or conference, and frequently writes blog posts, too. She is extremely responsive on chat, and answers all the questions her coworkers have when they pop into the team slack. Susan has a high profile in the community and her peer reviews are always sprinkled lavishly with compliments and rave reviews from cross-functional coworkers across the company.

these are qualitatively different from the obligation you have to your core job. If you did only your core responsibilities and none of the extras, your job should not be in any danger. But if you don’t do the core parts, no matter how many extras you do, eventually your job probably will be in danger. Explain to your coworkers that you need to hit the pause button on electives; they’ll understand. They should respect your maturity and foresight.

these are qualitatively different from the obligation you have to your core job. If you did only your core responsibilities and none of the extras, your job should not be in any danger. But if you don’t do the core parts, no matter how many extras you do, eventually your job probably will be in danger. Explain to your coworkers that you need to hit the pause button on electives; they’ll understand. They should respect your maturity and foresight. engineer. Maybe you just aren’t into the work anymore (if you’ve been there a while), or maybe you don’t know how to get started (if you’re new). Maybe it’s even as simple as mentioning it to your manager and reshuffling your responsibilities a bit. But don’t assume the problem will solve itself.

engineer. Maybe you just aren’t into the work anymore (if you’ve been there a while), or maybe you don’t know how to get started (if you’re new). Maybe it’s even as simple as mentioning it to your manager and reshuffling your responsibilities a bit. But don’t assume the problem will solve itself.

Some people eventually make peace with this, but many never do. No shame in that.

Some people eventually make peace with this, but many never do. No shame in that.